Isolation Conversation

Isolation Conversation

An Isolation Conversation with Chris Salamone, Lecturer in English

Read moreThe Elizabethan satirist, Thomas Nashe (1567-1601), repeatedly turned pestilence into stylistic profit. In The Unfortunate Traveller (1595), a darkly comic picaresque prose fiction, he spins out excessively vivid descriptions of the ‘hotspurred plague’ that struck Rome in the ‘vehement hot summer’ of 1522. Such moments, as with his fever-pitched, eschatological pamphlet, Christs Teares over Jerusalem (1593), draw on Nashe’s own experience of the violent infection that befell London between 1592-1593, when plague mortality rates surged in London’s overcrowded tenements and subdivided houses. Although this particular outbreak temporarily isolated Nashe from his usual networks of literary production, it also opened up new creative avenues, and opportunities for stinging satirical attacks.

Nashe’s movements in the late summer of 1592 were in some ways the inverse of Gabriel Harvey’s, the rhetorician and sometime-satirist with whom Nashe had an ongoing feud. He mocks Harvey in Have With You to Saffron-Walden (1596) for having holed up at John Wolfe’s print-house during the outbreak, arguing that he did so only in order to spitefully continue ‘ink-squittering and printing’ against Nashe. Located by St. Paul’s Churchyard and overlooking an over-spilling burial site for five parishes, Nashe is probably not far wrong when calling Wolfe’s shop ‘the hellmouth of infection’. Harvey is depicted residing here in the ‘ragingest furie of the last Plague, where there dyde above 1600 a week in London’:

‘cloystred and immured he remained, not being able almost to step out of doors, he was so barricaded up with graves, which besiedged and undermined his verie threshold’.

Harvey apparently found himself in this infernal isolation because of an embarrassing quid pro quo relationship with Wolfe: he had to both pay this printer to publish his own attacks on Nashe, and undertake various jobs while living with him, such as writing the post-script for Wolfe’s plague bills. No doubt, Nashe scornfully suggests, this profiteer ‘hop’d (belike) that the Plague would proceed, that he might have an occupation of it’.

By contrast, Nashe fled London, temporarily cutting himself off not just from printers, but friends, too. Harvey is quick to point out that Nashe ‘either would not, or happily could not, performe the duty of an affectionate and faithful frend’ (Foure Letters, 1592) when Robert Greene was on his death-bed in September of that year. Harvey’s accusation taps into a recurring motif in plague literature — the testing and breaking of social bonds and civic duties. Yet times of crisis also encourage new social ties to form in fresh contexts, whether that context is Google Hangouts, or, in Nashe’s case, a manor house in Croydon’s countryside. Escaping the city, he finds protective patronage under Archbishop John Whitgift, whose Croydon ‘Palace’ provided a space for refuge, creativity and, it seems, frustrated isolation. Whereas Harvey is mockingly portrayed imprisoned within the duel epicentre of the epidemic and print production, Nashe is shut off from both. In a ‘Private Epistle of the Author to the Printer’, included in the second edition of Nashe’s anatomisation of London’s vices, Pierce Penilesse (1593), he complains of the previous ‘uncorrected and unfinished’ edition’s errors. Nashe had been unable to oversee its printing because the ‘fear of infection detained me with my lord in the country’. Pierce Penilesse and its author are, in a sense, editorially quarantined from each other: ‘if the sickness cease before the third impression’, Nashe explains, ‘I will come and alter whatsoever may be offensive to any man’. Until that time, he wearily accepts that he must remain ‘the plague’s prisoner in the country’.

Yet we cannot consider Nashe’s time in Croydon during that late summer as one of total self-isolation, and nor did it imprison him away from occasions for literary creativity. His role within Whitgift’s manor appears to have been decidedly social and performative. Charles Nicholl asks us to imagine Nashe’s status here as ‘hovering ambiguously between guest and employee, scholar and showman’, citing an undated letter from a Puritan scholar who complains that Whitgift’s ‘Nashe gentleman scoffed my Ebrew studies’.[1] This period of employed scoffing also sees Nashe write his only solo-authored play, Summer’s Last Will and Testament. An allegorical piece mixing elegiac sentiment with irreverent humour, it depicts the personified, dying Summer, bequeathing his assets to Autumn, Winter and Spring. Its energy derives, however, mainly from the choric ghost of Will Summers, once fool to Henry VIII, who persistently derails and undercuts speakers with comic quips and meta-theatrical winks to the audience. A tonal hybridity therefore ensues as festive and funereal forces intertwine. The ‘doleful ditty’ sung at Summer’s request, now commonly anthologised and performed as the ‘Litany in Time of Plague’, is a case in point. In itself, the song sways between a general acknowledgement of transience (‘Adieu, farewell earth’s bliss’) and a refrain foregrounding the specific conditions faced by those still in London (‘I am sick, I must die; / Lord, have mercy on us’). But after six stanzas of unrelenting bleakness, the fool’s immediate response seems to subvert, even while recapitulating, the sombre tone:

WILL SUMMERS: Lord, have mercy on us, how lamentable ‘tis!

It is hard not hear the fool speaking the line in a spirit of mocking mimicry, an eye-rolling plea for light-relief from this emotionally exhausting theme, directed either at Summer, or even the ‘Lord’ of the house, Whitgift himself. Performed by members of Whitgift’s household, the play served as a private but communal entertainment when public theatres were closed due to the plague. This may explain the sense of festivity laced through its grave subject: partially shielded from the threat of infection, and with the plague’s peak ebbing as Summer draws to a close, Nashe provides Whitgift’s household, in semi-isolation, with a chance to perform and collaborate in an intermingling of medicinal laughter and lament. As we today encounter a daily refrain of doleful news repeated across social media platforms and set up online teaching forums to maintain social distance, perhaps Nashe’s frustrated, creative Croydon sojourn can both prompt us to find new forms of performance and collaboration in innovative (virtual) spaces, and remind us of the need for a little Will Summers-revelry to ease us through ‘lamentable’ times.

[1] Charles Nicholl, A Cup of Newes: The Life of Thomas Nashe (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1984), 136-7.

Although R. B. McKerrow’s five-volume edition, The Works of Thomas Nashe (Oxford, 1958) is not online, you can read digital versions of Nashe’s works

Find out more about each text mentioned, and the Oxford University Press edition of Nashe’s works

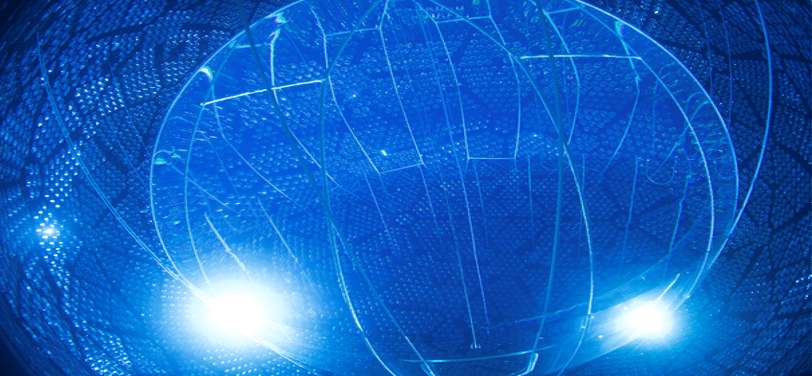

A full-recording of Summer’s Last Will and Testament, performed by Edwards Boys at the Great Hall of the Old Palace School in Croydon, can be found here. Note their take on the fool’s response to the ‘doleful ditty’ differs from my reading!